Ledgers: Humanity’s Longstanding Pursuit of Immutable Records

This blog explores how humanity’s pursuit of trusted records has evolved from tally sticks and temple scrolls to blockchain, reshaping how we secure information across time and scale.

We often associate ledgers with money, accounting, and finance. But ledgers are simply systems for recording information, and throughout history, humans have evolved countless methods to preserve records that could be trusted. From wooden tally sticks to digital histories on Google Docs, the way we record and protect data reflects how we build trust. In this piece, we explore the deeper story of ledgers, the centuries-old human pursuit of immutable records, and why technologies like blockchain are now redefining this pursuit at a global scale.

At first glance, the word ‘ledger’ probably brings to mind spreadsheets, balance sheets, or bank statements. It’s a term we often associate with finance and accounting, where trust and accountability are absolutely essential. But at its core, a ledger is something much more fundamental. It’s simply a way of recording information: what happened, who was involved, and when. And that basic function shows up in more places than you might expect.

Where Else Do We Find Ledgers In Action Beyond The World Of Finance?

Ledgers help track land ownership in 1cadastral maps, log supply chain activity in global logistics, store patient histories in healthcare, document creative rights in intellectual property, and manage digital identities in governance systems. Long before ledgers were digital, financial, or even written down, human societies used them to make sense of agreements, obligations, and shared truths. Across all these examples, one thing stays constant. The goal is to preserve information in a way that people can trust, not just in the present, but for years to come.

What Makes A Ledger Truly Trustworthy?

A defining feature of a trustworthy record is immutability, the idea that once something is written, it cannot be changed without leaving a trace. While the word may sound technical, the principle is intuitive. After all, why record something if it can be quietly erased or altered? Immutability is not a mere feature of a ledger, it is what defines it because a ledger, by design, is meant to be immutable. From ancient civilizations to modern cloud platforms, the integrity of any ledger depends on its ability to reflect the truth reliably over time. Whether etched in stone, carved into wood, or stamped into code, ledgers work best when they cannot be tampered with.

Let’s look at how this instinct has played out across time.

How Did People Keep Records Before Paper and Databases, and How Has Record-Keeping Evolved Over Time?

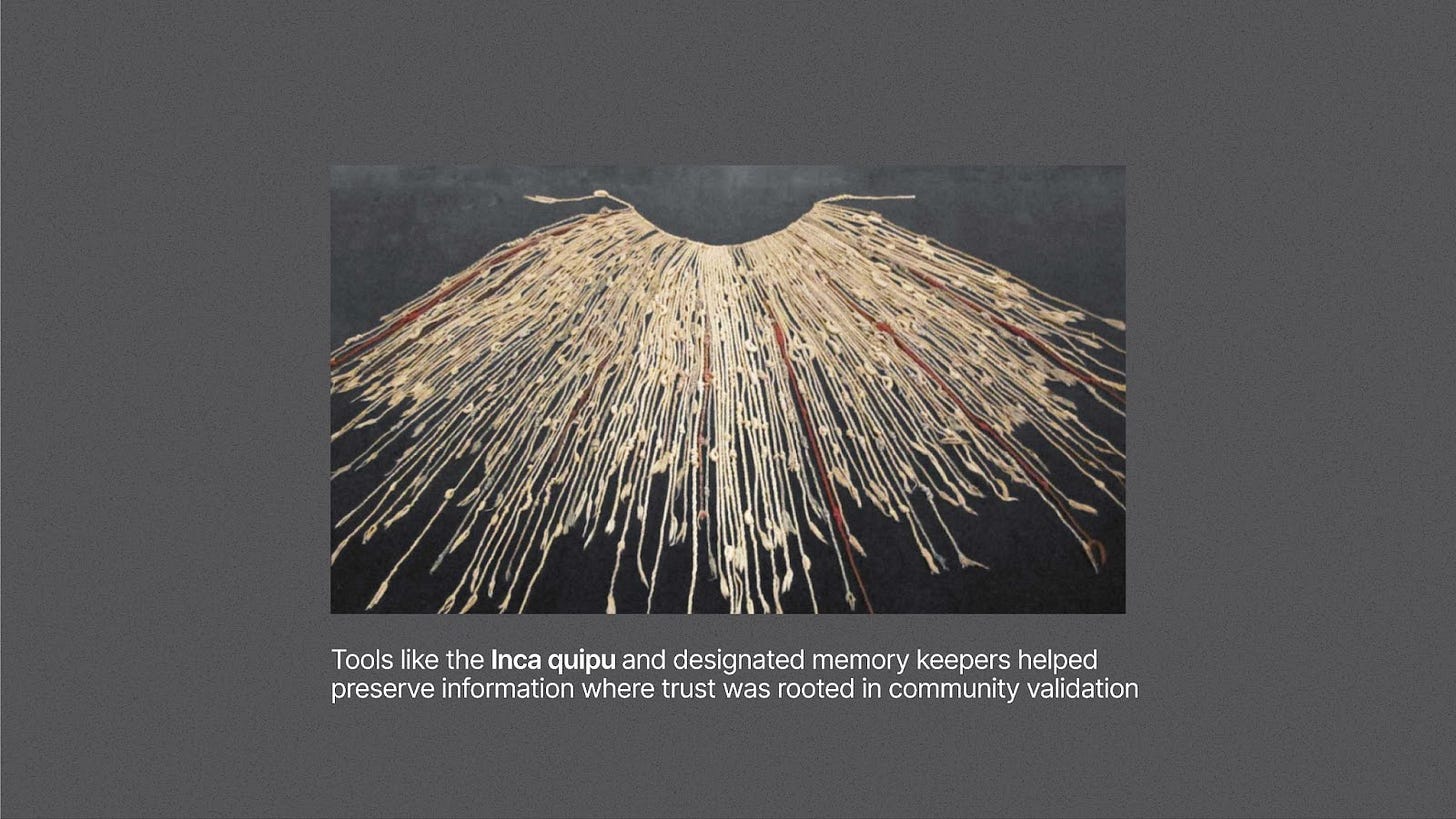

The instinct to preserve trustworthy records is as old as human society. In prehistoric societies, oral traditions and physical markers served as early memory systems (Assmann, 2011). Tools like the Inca quipu and designated memory keepers helped preserve information where trust was rooted in community validation (Urton, 2003). With the invention of writing, ancient civilizations like Sumer and Egypt transitioned to clay tablets and scrolls. Temple scribes and monarchs became custodians of truth, marking the beginning of institutional record-keeping (Goody, 1986; Oppenheim, 1964). Across the world, other innovations emerged as cultures developed their own trusted mediums and practices for preserving records.

In medieval England, tally sticks split pieces of wood used to track debts were naturally tamper-evident and remained reliable for over six centuries. Ironically, a failed attempt to dispose of them by burning triggered the 1834 fire that destroyed the British Parliament, illustrating the vulnerabilities of centralized physical storage.

In India, generations of shopkeepers used bahi-khata, handwritten ledgers maintained within tight-knit communities. These records were often verifiable and respected, but they relied on personal reputation and remained vulnerable to damage, loss, or misinterpretation. Despite their differences, both systems aimed to create records that could be trusted over time and across parties.

As societies grew more complex, so did their record-keeping needs. Paper-based tools like stamped registers, land records, and trading logs began to formalize accountability through legal and bureaucratic systems (Yates, 1989). The rise of digital infrastructure in the 1980s introduced centralized databases, spreadsheets, and cloud-based platforms. These systems offered unprecedented speed, access, and convenience, but still depended on the authority of a single organization and remained prone to tampering or technical failure (Beniger, 1986; Kahn & Cerf, 1988).

Fast forward to today, and we find ourselves using digital tools that carry forward our quest for transparency and verifiability. Google Docs, for example, allows users to track version history, where each change is recorded with time and identity (Google, n.d.). Amazon provides time-stamped receipts for every transaction, simplifying returns and disputes (Amazon, n.d.). Health apps log daily metrics like medication, sleep, and activity to ensure continuity and prevent data manipulation (Luxton et al., 2011). Fintech platforms generate automatic audit trails that help both consumers and institutions reconcile events with confidence (Arner et al., 2017). None of these are labeled as ledgers in the traditional sense, yet they fulfill the same core function: capturing and protecting records from silent revision.Ledgers still serve the same purpose, and today, they can do so at a scale and speed that was once unimaginable. The story of ledgers is a story of ever-strengthening trust. Today, technologies like blockchain are making this feature more scalable, more transparent, and more decentralized than ever before. More on this in the next section.

If We’ve Always Used Ledgers To Build Trust, What’s Unique To Our Times?

Throughout history, societies have evolved their methods of record-keeping. These began with oral memory systems, moved to tamper-evident physical tools like tally sticks, then to institutional paper records, and eventually to centralized digital systems. Each stage brought improvements in how quickly and reliably we could capture, protect, and share information.

But today’s digital infrastructure, while powerful, brings its own set of challenges.

Most modern systems rely on centralized servers or cloud platforms. While these are efficient, they come with vulnerabilities. Servers can crash, data can be altered or lost, and cyberattacks can expose sensitive records. Access may also be restricted by geography, regulation, or institutional gatekeeping. These problems are not usually caused by bad actors but stem from limitations in how the systems are designed. Take the 2017 Equifax breach, for instance. Personal data from 147 million Americans was exposed due to a security failure (Hern, 2017). Or the 2019 Capital One breach, which compromised the financial data of over 100 million customers (Zengler, 2019).Both cases show how centralized systems, no matter how sophisticated, can become single points of failure.

What Do These Failures Tell Us About The Bigger Challenge?

Incidents like the Equifax and Capital One breaches reveal a deeper structural flaw in how we store and manage information. As our world becomes more interconnected, the challenge is no longer how to record information, but how to ensure it remains tamper-proof, accessible, and verifiable across time, institutions, and borders. When systems are tightly linked across sectors and geographies, a failure in one part can create ripple effects far beyond its origin. From global supply chains to international banking, we need record-keeping systems that are not only efficient but also resilient and trustworthy at scale. This is where the next phase of trust infrastructure comes in: systems designed not just to store information, but to secure it against manipulation at a global scale. Enter 2blockchain. Blockchain builds on the idea of the immutable ledger but takes it further by distributing records across a network, rather than storing them in a single location or under one authority. Each record is time-stamped, 3cryptographically linked to the previous one, and validated through consensus, making it difficult to alter without detection. Blockchain is the digital evolution of trusted record-keeping systems humans have relied on for centuries, offering greater scalability, transparency, and decentralization.

In the next part of this series, we’ll explore how blockchain offers immutability, transparency, and shared trust to meet the needs of our interconnected world.

References:

Arner, D. W., Barberis, J. N., & Buckley, R. P. (2017). FinTech and regTech in a nutshell, and the future in a sandbox. Research Handbook on FinTech and Artificial Intelligence in Finance, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3020723

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural memory and early civilization: Writing, remembrance, and political imagination. Cambridge University Press.

Beniger, J. R. (1986). The control revolution: Technological and economic origins of the information society. Harvard University Press.

Catalini, C., & Gans, J. S. (2016). Some simple economics of the blockchain (No. w22952). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22952

Google. (n.d.). Track changes and version history in Google Docs. Retrieved March 27, 2025, from https://support.google.com/docs

Goody, J. (1986). The logic of writing and the organization of society. Cambridge University Press.

Hern, A. (2017, September 7). Equifax breach exposed personal data of 143 million Americans. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/07/equifax-breach-exposed-personal-data-of-143-million-americans

Kahn, R., & Cerf, V. (1988). What is the Internet (and what makes it work). Open Architecture Initiative: https://www.cnri.reston.va.us

Luxton, D. D., McCann, R. A., Bush, N. E., Mishkind, M. C., & Reger, G. M. (2011). mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024485

Narayanan, A., Bonneau, J., Felten, E., Miller, A., & Goldfeder, S. (2016). Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: A comprehensive introduction. Princeton University Press.

Oppenheim, A. L. (1964). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a dead civilization. University of Chicago Press.

Urton, G. (2003). Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary coding in the Andean knotted-string records. University of Texas Press.

Yates, J. (1989). Control through communication: The rise of system in American management. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Zengler, T. (2019, July 29). Capital One breach: What you need to know. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomzengler/2019/07/29/capital-one-breach-what-you-need-to-know/

All artworks are designed by Sanjivni Dwivedi & Himanshi Parmar

If you enjoyed reading this blog and would like to receive more such articles from Scaling Trust, please subscribe to our blog using the link below:

Alternatively, know more about us on our website here.

Keep in touch with us on: LinkedIn | X | Telegram | Youtube | Email

Cadastral maps are detailed maps that show the boundaries and ownership of land parcels. They are part of what's called a cadastre, which is an official record of land ownership, property boundaries, and value, often used for taxation, legal ownership, and land management.

These systems shift the foundation of trust away from personal reputation or institutional authority and instead embed it directly into infrastructure. By distributing records across networks and securing them with cryptography, blockchain enables globally verifiable, tamper-resistant data by default.

Cryptography refers to the practice and study of techniques for secure communication, often involving converting information into an unreadable format (encryption) to protect it from unauthorized access.

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No huge reader base Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, truth, vision, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

Built to Be Left.

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e